Located in the Sierra Tarahumara, southwest of the state of Chihuahua (Mexico), in a region known to be hard and difficult for life is the ethnic group Rarámuri. The Rarámuri, also known as Tarahumara, with a population that, according to the census of 2000, reach 86,588 individuals1, live among the mountains and the gorge, maintain a highly dispersed settlement pattern and a subsistence economy based on the agriculture and grazing (corn crop and especially goat husbandry). This ethnic group has in the dance one of its most genuine forms of expression and communication; dance that in its various manifestations (matachines, pintos, pascol, jícuri, bacánowa) has been orientated to both the divine worship and human relations, demonstrating to possess in any case a high practical sense that does not lack a symbolic component.

Based on data obtained during eleven months of field experience in various placements between 2001 and 2003, spread over several Rarámuri communities of the high and low Tarahumara, the attention will focus here on pascol, Rarámuri dance that, as the case has both human and divine guidance.

First we will provide some historical and ethnographic references on the matter, characterized the pascol then, that is practiced extensively in the canyon, and then do the same with which specifically takes place at a particular place in the mountains, and end up with the search for the meaning of all this mise en scene.

Historical and ethnographic references

For the reports obtained of some researchers, everything seems to indicate that the dance of pascol or pascola existing in the Tarahumara comes from the groups Yaqui and Mayo of the northwest. This way Velasco understands it on having raised that:

Probablemente era un danza que los misioneros encontraron e integraron a la liturgia desde antes de su “entrada” a la Tarahumara y que fue importada a ésta, sea por los mismo Jesuitas, sea –más probablemente- por los indígenas de las tribus ya evangelizadas, que acompañaban a los misioneros en sus incursiones a tierras nuevas. Hay que recordar que los Jesuitas pasaron de las misiones de Yaquis y Mayos a las de Chiapas y Baja Tarahumara2.

In turn, while Gonzalez Rodriguez3 believes that the Pascol of Norogachi is a replica of the dance of the deer among the Yaqui, Bennett and Zingg4 attribute a Spanish origin to it: The pascol, also of Hispanic origin, is a very fast footwork. Therefore, in its origin, it would be a foreign dance to the rarámuri culture. However, Breen Murray understands that the symbols that it has are not Catholic, but generated by the Indian philosophy: “[…] these symbols bear no direct relation to the tradicional Hispanic Catholic symbols of Easter, and this strongly implies that an esoteric meaning in purely indigenous terms must exist (or have existed)for this symbol complex”.5

The term used to describe this kind of dance is very probably a variation of the Spanish word “Pascua” (Easter), a period in which it usually is performed more frequently, taking as a colonial origin brought by the missionaries6, even when the content of the dance has indigenous roots. An interesting and accurate definition of pascol or pascola was found in a letter written in the National Indigenous Institute (INI) of Guachochi in May 16, 1960:

Generically it is named Pascolas to the music of the Tarahumara region, mainly in the gorge, which serves as an accompaniment to the dance that runs the pascoleros.

These are pace sounds of varied tunes whose themes are very broad and ranges from owls, roosters, pigeons, quail, songbirds, deer, rabbit; although the music is not exactly onomatopoeic, designed to interpret sounds similar to the singing of the rooster, the murmur of the dove and gives the idea of the concerns of deer and the attitude of the rabbit. Notwithstanding the foregoing, there is music whose theme is the woman who stays at home when the man goes to work, accompanied by her dog and her cat, and Owirúame -or Indian doctor- who is curing a patient, or the goatherd, who lost his goats.

Later continues with the story of animals and situations, which they represent according to a specific calendar and schedule:

[…] Then the pascolas continue: Coyotes, to be played in the evening or at night, and the goatherd, theme related to the coyote, which aims to eat the goats; the owl, to be enforced well into the night distinguishing two roosters, the young rooster and the old cock. “The cuichi” or chicken of the countryside, who sings as soon as the morning starts clarifying. “The chuparrosa” (type of hummingbird) that shakes its wings to escape the sun; “the churea” which is the pheasant, who runs roads that will sing later; “the auras” or hairless head vulture, other than the white wings vulture that starts to haunt the sky late in the morning. “Crows”, “Quail”, “The dove”, “The songbirds”; “Cranes” who come from far away and that is why they dance later. Rabbits, deer, “The Hicos” or lizards, “The Cachora” or chameleons, “Pascola the cheerful”, the skunk, “the cholugo” or raccoon, goats, young goats,cow and hatchlings, the bull, squirrels and pine fence; The woodpecker, the piece that the pascolero dances when he is very tired of having danced a day or more. In addition “Charity”, music with which the musicians and dancers ask “corima” from those attending the festival, finally themes like the woman who cares for the house accompanied by a cat and dog, while the man is working; and the Tarahumara doctor who is taking care of a sick person.7

The pascol even when practiced especially around Easter, are dances that liven up the festivities in the low Tarahumara. Tranquilino Cruz Sinaloa, a 54 year old rarámuri, native to Huetosákachi (Municipality of Bocoyna), describes it as follows: “The pascol dance is for rejoicing, we dance it more on the feast of Easter, along with the Peróchi,(grandfather on the mother side) name given to the monkey straw that represents Judas on the Holy Week, and we, the Pharisees, walk thru the houses collecting the food that we will eat during the festivities.”8

For Wheeler is a cheerful and energetic dance, and this is how he describes the dance of the pascol of Luciano:

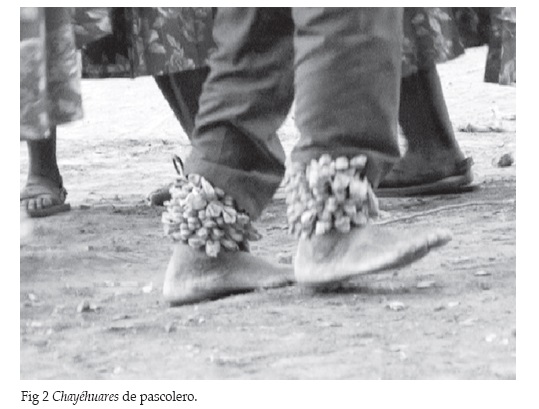

He ties up the “chaníbares” -a tape with butterfly cocoons filled with seeds9 – around his ankles and starts to give more joy to their dance. Sometimes his feet seem to be more time in the air than in the ground. With challenge he hits on the heels the hard trampled land. Hiss like a cat scratches the ground with his foot on the floor and turns around again, encouraged by the joyful cries of those who are watching, those who lead him to a big frenzy.[…] suddenly makes a sharp scratch on the floor with his foot and abruptly ends his dance.10

Within the context of the Easter holidays, the pascol of Norogachi, the only dance itself from the high Tarahumara, acquires very unique characteristics that differentiate it from the lower mountains in its various forms. A rarámuri-mestizo speaker and former Jesuit, resident in Norogachi, for whom the pascoleros possess the role of being heralds of the resurrection of Jesus Christ, offer a good description of the context in which it is realized, during a field interview. [This interview was not translated in order to respect the essence of the words used by the interviewed]:

[…] el rito de la resurrección es muy simbólico también, los pascoleros llegan hasta la plaza en donde ya previamente han puesto el Judas y lo pusieron allí en el atrio de la Iglesia, llegan los pascoleros y bailan frente a la iglesia tres veces, de la iglesia se saca toda la gente, no queda nadie dentro más que el sacerdote que está mero delante en el altar [en realidad entran todos los que van con los pascoleros con la cruz en la frente]. Entonces nada más entran los dos pascoleros, el tamborero y el músico, entran solos bailando haciendo caracoleo adentro, y el símbolo más propio que no se hacen todos los años porque es difícil hacerlo, es que el día antes los soldados comenzaron a buscar en el monte, en los cercos un chulépari un pajarito así chiquito con el pico largo [no es colibrí], y de esos pajaritos agarran dos, uno vivo y el otro muerto. En la primera entrada que hacen los pascoleros bailan una vez y salen hasta fuera de la iglesia, entran de nuevo y bailan una segunda vez, de nuevo salen afuera; a la tercera vez que bailan dejan un pajarito muerto en el altar enfrente del paso, entonces descansan y entran solos de nuevo y bailan entrando y saliendo tres veces como antes, y al entrar la tercera vez sueltan un pajarito vivo dentro de la iglesia, que es la seña de la resurrección. Entonces el pajarito queda volando, salen los pascoleros y a la siguiente entrada de los pascoleros entra todo el pueblo. Antiguamente en ese momento se celebraba la misa de la resurrección, actualmente ya no se espera a la misa, se hace una cosa eterna la misa, al salir los pascoleros van directamente a matar al Judas. Lo que pasaba también es que durante unos años se celebraba la misa, los pascoleros durante la misa están inactivos, están encuerados, entonces salían e iban a su rincón, en un rincón de la plaza tienen un lugar propio, desde que comenzaron a pintarlos ya se toma tesgüino, entonces ya la costumbre fue que la gente prefería ver a los pascoleros y no quedarse a la misa y poco a poco la misa fue perdiendo hasta que quedó muy reducida, entonces ya se hace la ceremonia de la muerte de Judas, pues.

El pascol de aquí (Norogachi) es distinto del pascol de la barranca, el pascol de la barranca participa en casi todas las fiestas junto con matachines, participan hombres y mujeres en una gran fila que se hace con un culebreo junto a la cruz, allí es otro tipo de celebración de la pascua, el pascol es eso, pascolero, aquí son dos personas que bailan únicamente esa noche y acabando de bailar ya no vuelve a bailarse pascol, es una cosa sumamente solemne y sagrada y nada más tiene su función en anunciar la resurrección. Es muy difícil, muy cansado, lo suele hacer gente mayor, son pocos los que saben hacerlo, hay que darles una atención muy especial, cuidarles que no pisen una piedra, en fin, bailan descalzos, seles tiene que dar de comer, darles tesgüino también, y es la única ocasión, aquí en esta región.11

On the other hand a well-illustrated Rarámuri, based in Rosánachi and for who the pascol is essentially an indigenous fertility dance, we described another of the over-the-field interviews some of its key symbolic and some reasons for change over time [This interview was not translated in order to respect the essence of the words used by the interviewed]:

A los pascoleros de Norogachi en las articulaciones del cuerpo se le pinta una cruz en las manos, una es la hembra y otra es el macho, uno va pintado de rojo y otro de negro. Llevan dos rayas, esta es un rojo y esta es un negro, en la otra parte del cuerpo en lugar de la raya negra es la raya roja, aquí hay una cruz negra, y en la otra pareja en lugar de la cruz negra tienen la cruz roja, uno tiene los pies rojos y la otra pareja los pies negros, uno tiene los pies negros, las manos negras y las cruces negras, y el que tiene los pies rojos tiene las manos rojas, las cruces rojas y la raya que va de la cruz pa arriba es roja también, y el negro va igual de negro, entonces es el día y la noche, el bien y el mal, la hembra y el macho, y así antes bailaban, cuando se ponían todos bailaban, el negro delante, era la noche pues, era la hembra, la danza era más bien una especie de cortejo pues, de hembra y macho, y hasta los movimientos y todo, pero ya en la media noche se asimilan todas las funciones del macho, del rojo, porque ya venía el sol e iba a amanecer, y hasta que amaneciera, hasta que venía el sol y por el día se seguía bailando, pero todo tiene su significado en la danza del pascol, hasta la pintura.

[…]La pintura de los pascoleros en Norogachi dura como toda la noche, comienza como a las 7 u 8 de la tarde y terminan como a las 12 de la noche, tan tarde, porque va por etapas. Las mujeres no se pintan, aunque al inicio del pascol dicen que era una mujer y un hombre, pero desde la entrada de los misioneros se quitó porque los misioneros [no pueden] ver a una mujer desnuda bailando, verdad, y es que tenía que ir enseñando los senos.

[…] El pascol [de Norogachi] sí es danza autóctona, pero el fariseo y el pinto, bueno el pinto era una danza de guerra que se usaba antes aquí en la Tarahumara, pues incluso los instrumentos del tambor y la flauta de carrizo son instrumentos y música de guerra.

[…] El pascol sólo se baila en la noche de Pascua, en la noche de Gloria, pero como aquí éste, con la intervención de los curas se cambió, se adelantó, y sólo el viernes en la noche bailan, del viernes al sábado, antiguamente era del sábado al domingo. Se ha ido perdiendo una parte de esta fiesta del pascol, que con los misioneros es un símbolo de la resurrección; eso dicen los misioneros, pero para la mentalidad indígena tiene otro significado. Los pascoleros son los que bailaban el sábado en la noche para amanecer el domingo; entonces, en el momento en que en el mundo cristiano se canta el Gloria, no, es la hora de la resurrección a las 12 la noche. Aquí hay un pájaro muy parecido al espíritu santo, así medio chiquito, un pájaro que anda por aquí y le decimos santapagó; entonces los soldados son los que cuidan a los pascoleros, entonces se iban todos los soldados de aquí de Norogachi para agarrar un pájaro de esos, entonces esos pascoleros bailaban el sábado en la noche antes de que cantaran el Gloria, entonces llegaban los pascoleros y le colocaban el pajarito aquí en el hombro al padre y de ahí volaba y era el momento de la resurrección, ese pájaro suyétar [en rarámuri]. Esa parte ya no se hace ahora, pues como ya no se espera a la misa de resurrección, se va la raza, esa parte ya se perdió, por supuesto que era impuesta, no es rarámuri pero era digna de observar.12

The pascol of Norogachi (high Tarahumara) is thus a model very different from the pascol dance in Cerocahui, Urique and other villages of the gorge or low Tarahumara, as well as various styles of dance are both the pascol Rarámuri with respect to the practiced by the Mayo and Yaqui, usually done by a specialist who wears a special outfit.

Characterization of pascol Rarámuri in the low and high Tarahumara

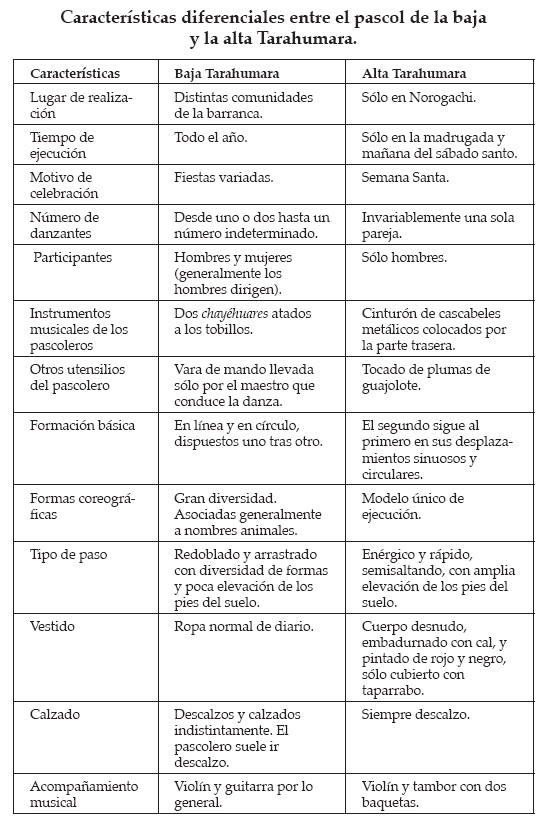

To provide a more complete picture of the styles of dance performed by the pascol Rarámuris, then describe the cases in two regions: both in the low Tarahumara, with very different dynamics, and Norogachi, an area of high Tarahumara and whose performance conforms to a single model. However, it should be known before the marked differences in the structure and function of pascol done in the low and high Tarahumara. To that end, we present the table on next page.

Pascol in the low Tarahumara13

Area of achievement

Inside the church, courtyard outside the temple, courtyard houses, open field, anywhere can be used for dancing pascol.

Time of completion

Any time of the day or night.

Reason for celebration

Any kind of community festivals and family celebrations.

Participants: number, age, sex

Number of dancers not specified, of both genders and all ages. Participation is open to anyone and intervenes between one and forty dancers.

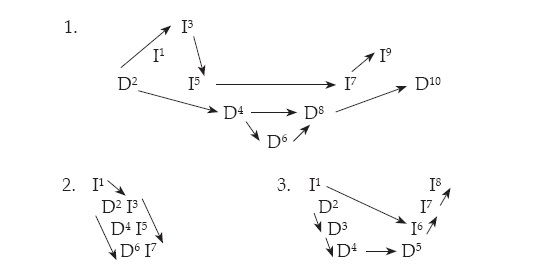

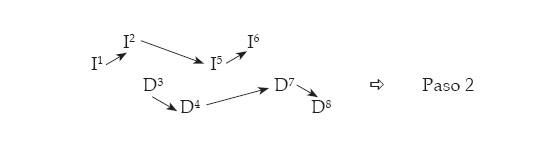

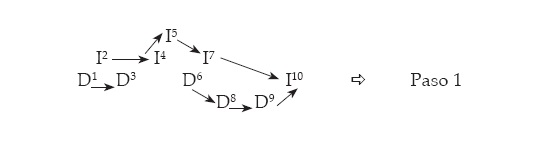

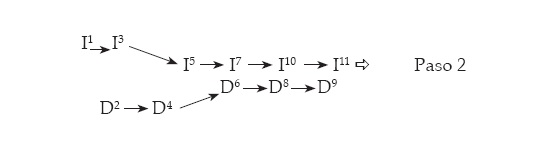

Choreography: structure and dynamics

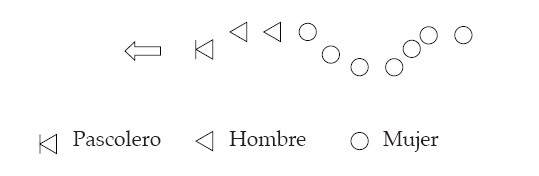

General structure of the group of dancers: pascolero the first, second men and women in the third.

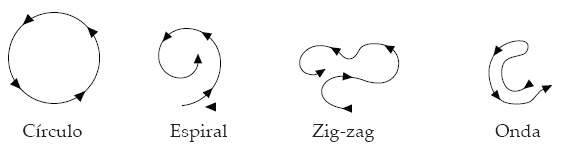

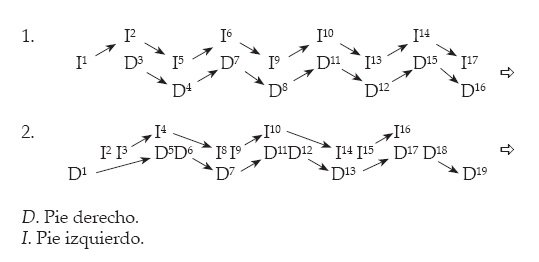

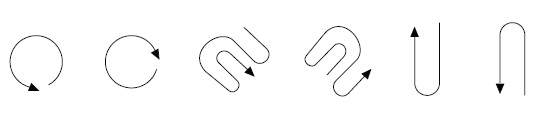

Some routes of the journey. All are made in both directions.

The pascol is dance in sets of three pieces of different lengths, although usually each lasts ten to fifteen minutes. Between series, there is a more or less prolonged rest.

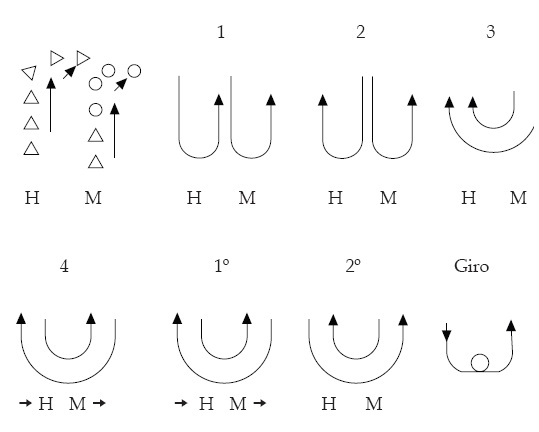

Uniqueness of San Alonso (Urique): In a row, the first man and up to the last woman rotate 360 degrees in counterclockwise direction, while moving forward. After the turn of the last of the row, for the second time on tour the pascolero goes to the head and ends the round. Otherwise the turns of 360 degrees (always in counterclockwise direction) are conducted every one to each discretion, without an order and without the initiative of the pascoleros. To make a new figure will form two groups: one for men, with pascoleros to the head, and another of women, both are placed in parallel to move forward or backward at the same time, either in the same or different direction. To compensate for the number of dancers per group, two men were placed at the end of the row of women. The initiative on the route or direction to follow is of the pascoleros, the first one makes a sign with his cane showing the way both groups have to follow. To indicate the end, the pascolero will lift his hands up and that will stop the music and the dancing.

Alternative movements

1. The two groups change direction on the left side

2. The women’s group changes its direction on the left side and men on the right side.

3. Both groups change direction on the right, the men wrapping the women.

4. The group of men wraps the women by moving in the opposite direction. In order to establish complementarily and opposition movements in both groups, the men wrapped first the women to the outside, crossing in opposite directions (1), then the positions are reversed and women wrapped the men crossing in the opposite direction (2nd). In the curve of the track, the dancers sometimes revolved about themselves inwards 360 degrees, to continue moving forward (spin).

Steps and body position

1. Cerocahui

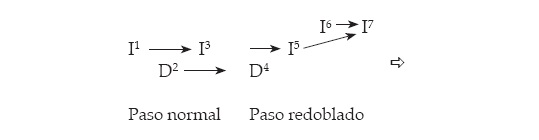

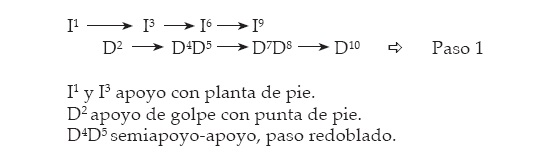

Mixed steps with a characteristic beating, the body’s weight rests more on one foot than in another. The pascolero marks the step and the route to follow. His step is more colorful and complex as those of the rest.

In the standard step, there is a double support to each foot (semi-support/support), with very short steps, glued to the ground and continued. In the semi-support, the foot is taken alongside and parallel to the other, while in the support is separated the same foot forward making it move out, movement is made with both feet. Thus, advance happens with slight swaying to one and another side, as he never stays static. The semi-support is done with the front half of the foot and the support with the whole plant; the movement is always forward.

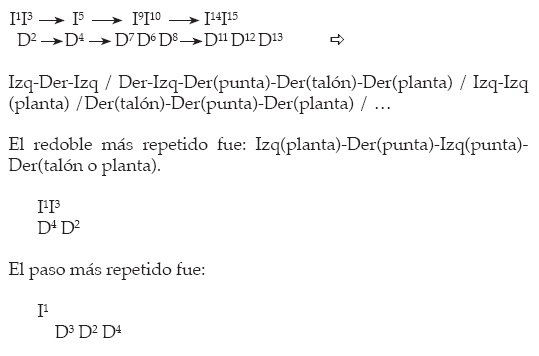

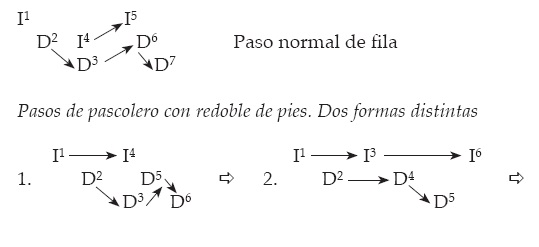

The body is kept straight or slightly bending forward or to one side. The arms are falling on both sides as abandoned, with little movement, especially in women; men can be seen also, with their hands in their pockets. The look is kept low to the ground. Cadence of the normal passage of the dancers:

Order of support

Step 1 is more frequent than 2. In case 2 is a peal of heel with two contacts followed with the support of the sole, either in one or the other foot. As a variant is sometimes step 1 and 2 alternated, so that with one foot there are two semi-support/support and the other a semi-support/support, and vice versa. Both, the dancers and the pascolero, run this. There are those who exaggerate the movement flexing and stretching the legs a bit on the steps, moving hips and body to one side and another, stomping. There are also those who do not move the body and only move the legs, adopting a very peculiar position with the head lightly inclined aside.

Cadence of the redoubled step of the pascolero

1. With two feet Alternate: support rapid redouble: L1 3, R2, R4 6, L5, L7 9, R8. For the record, you can see the continuous rotations that take place on either side. This step is the most common among those seen.

2. With two feet continuous (right and left interleaved.

3. With one foot (first right and then left).

The pascolero tends to bend the body forward more than the rest of dancers, moving with a slight twist to either side, or keeping his head down with an eye towards the ground in some cases, while others kept an eye to the front and head straight with a serene expression. The legs slightly bent, the hip slightly down and a hand falling aside without movement and the other holding the stick.

2. Wapalaina

Otherwise, the support in the standard step is more pronounced with the toe, the heel is used only for a faster movement. In the redouble step, the support is on the heels and sole, but other times the redouble is support only on the toes.

At the end of each piece, in communities such as Guagueibo or Cerocahui the pascolero supports the left foot, maintains a slight deflection of that leg, puts the right leg straight and scratches with the heel of the foot several times the floor from front to rear, indicating that gesture that stops the music and dance. Otherwise, the end of the piece can also be marked with the footwork of an alternate and another foot on the place, without any movement, or by dialing two-stroke support on the same footing and then be quiet.

Among the dancers, there are those who exaggerate more than other body motion. While some of them are moving around like statues, others are turning continuously on either side with the torso bending. Among the pascoleros everyone has their own style.

Some move as if they were seating, with legs slightly bent, small steps redoubled, straight torso and an abstract look, lost in the infinite, with arms falling on the side and a cane in the right hand. Others, however, revolve more on either side, the torso and head slightly tilted downward, look gaze to the floor, making it clear that there are very different styles.

3. Guagueibo

Usually the torso is straight and slightly leaned forward, but sometimes turns to either side, stretching and flexing and producing a greater variety of movements.

Step Cadence. Left sole support 1,3,5,7) and right heel semi-support (2,4,6,8), giving small jumps in circular direction from one side to another and then repeats the movement, but changing the weight foot. Is repeated again but the support is done with the toe (metatarsus) in front or in parallel to the weight foot. Repeats once more with toe (metatarsus) semi-support, but this time behind the weight foot, always jumping and moving forward. This gives the impression of moving forward only on one foot. The steps are made with slight bend of the legs, stretching more when it relies on the heel.

The dancer who goes back usually imitates the movements of the one in front, but because of speed of the movement, it sometimes seems uncoordinated, out of pace. They also performed complementary movements, for example, the one in the front supports on the heel and the one in the back supports on the toe, the steps mentioned above alternate freely. The end of the piece is marked with a slight jump, supported on the right sole, with slight bend of the right leg and the left leg stretched with the left heel scraping the floor twice.

4. San Alonso (Urique)

They advance a foot after other one alternating the approximation and the separation between both. It is marked strongly like stamp, raising approximately 10 cm of the soil.

Two steps with every foot mark a semi-support/support of an alternate way and always forward.

In none of two steps a straight path follows, so the pascoleros like the rest of the row are drawing with their bodies a sinuous line or in zigzag. Some mark more the oscillations of the step to one side and the other. The movements are realized by a slight flexion – extension of the body in every step and all to the pace, the arms are lose to the sides; the head of the women slightly tilted downward, the look down and the body slightly inclined forward. The roll of feet, more accentuated in the pascoleros with their chayéhuares tied to the ankles.

5. Huetosácachi (Bocoyna)

Short steps forward, about 5 to 10 Cms. per step, sometimes marked on the place. Sometimes the movement forward is larger, of no more tan about 30 cms. Legs are bending, the torso straight but slightly lean forward, head tilted down, and arms falling aside sometimes swinging, hips down, well balanced and supported on the floor. Feet are risen about 5 cms from the ground.

The end is marked with two stamps, scratching with the heel of one foot on the floor from front to back, the musicians stop playing. The beginning of the next piece was marked by a standing position with hands caught behind, in front of the musicians. From there he starts dancing, making a few steps marking a circle.

This step was similar for the second and third pieces but with a different pace, according to the music. Each piece lasted about 7 minutes. The constant was: step, step up, step, step up, step up … To facilitate a foot, the body is tilted to one side at times, to download the weight on one leg more than in another.

6. Samachique

Four consecutive steps alternating left, right, and a redoubled with the right; follows the cadence of footsteps with the left and so on. The support is done with the entire sole and it moves very close to the ground without lifting more than 5 cm. For the speed of the supports, the redouble remains practically all the time between one and the other foot. The advance is about 5 cm-by-step, and supports are made on the same place. Displacements occur with advancing side, forward and diagonally, usually drawing a small circle.

The stop is produced by two strokes with a foot and a hit with the other, all well marked, at which time music stops. The start of the next piece begins when they mark a circle with few steps and then directly mark the passage of dance.

If the rhythm of music demands it, sometimes exaggerates one step more (support), which is often the case after redouble stand: right-right (redouble)-left (high).

The body remains almost motionless, just move the feet with short steps. Slightly bend legs at all times, without reaching full extension, arms still owed to the sides, the torso tilted slightly forward, with low head.

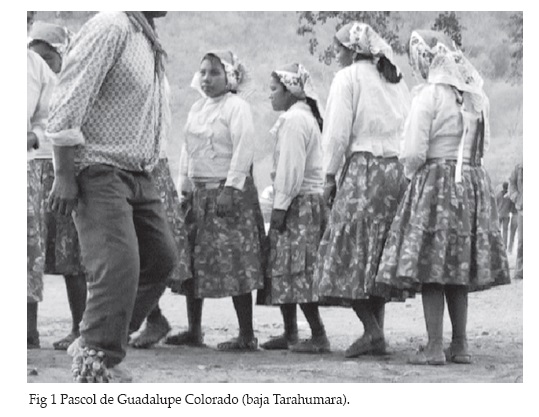

7. Guadalupe Colorado

The pascolero is the only one who is redoubling step and stamping the heel. Progressing with his legs slightly bend at all times, straight torso or leaning slightly forward, with slow and static, hip and slightly lower flanked, with sole support. He maintains a total synchronicity with the whole group, moving all together as a block making circles and moving forward, with a slight sway on both sides.

Paralenguage: facial expression, gestures, proxemics, musical instruments.

The right hand, at one end, holding it almost vertical and unsupported to the ground, holds the pascolero’s cane or stick. The men removed the hat to join the dance, while the women dance with a neckerchief on. There are those who carry their heads slightly flanked on one side all the time, especially frequent gesture in some women. Look serious, oriented to the ground or in front, expression serene and relaxed. The separation between participants is from 30 to 50 cm. approximately. The synchronized movements give the impression that the row rocks.

The musical instruments used can vary, although the minimum includes at least one violin and a guitar. The background environment varies depending on the place, time and reason for celebration. In some cases predominate the expectation on one or two pascoleros dancing alone, while in others it is the participation of all and all those present.

Pascol in the high Tarahumara

Place of performance

Norogachi. House of the alapérusi; path to the church; inside the temple; courtyard: outside the church. At the dance on the place (house of alapérusi) the dimensions of the space is about two meters in diameter, and in the other places, space wide to will of the dancers. The patio or place for the dance is cleaned of rocks and dirt or covered with a blanket in order to dance on it.

Time of performance:

Good Friday in the evening and early morning of Easter Saturday.

Reason for celebration

Holy Week

Participants: number, age, sex

Two men of different ages. Easter in 2003 involved a 40 year old and an 18 year old, combining experience and youth.

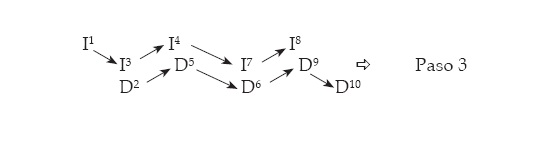

Choreography: structure and dynamics

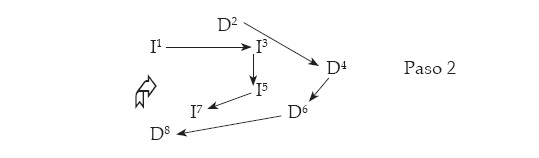

Some usual routes of displacement within the dance courtyard:

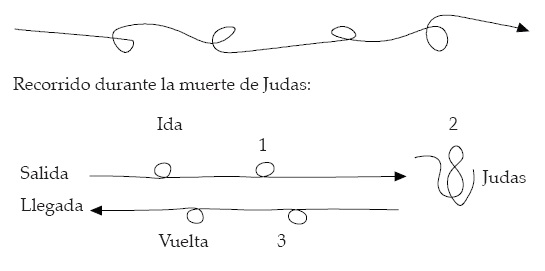

During the distance of the house of the alaperusi up to the church, the pascoleros, without becoming detached one of other one, are dancing most of the time to the pace of the music, describing linear and circular movements forward alternately.

1. One after another began to walk about four or five meters, then dance for about seven or eight meters long steps, and intersperse two circular movements on the journey.2.Sinuous and circular movements before the effigy of Judas. Whom they hit some blows, arousing laughter in the audience. 3. Turned to the place wherefrom they left in a straight line, marking again two small circles in the distance, always counterclockwise turn.

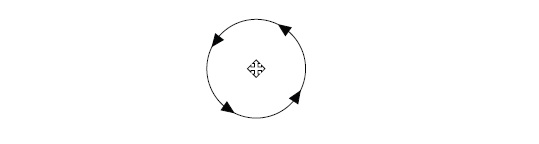

During the displacements of going and return the tamborero, and some soldiers accompany the two pascoleros along with the alaperusi or major standard-bearer (Organizer of the Holy Week), the polisio (executing arm of the alaperusi), as well as friends of Christ and enemies of Judas and of the pintos. Final tour in house of the alaperusi:

Circular route around the Rarámuri cross, in counterclockwise direction, with the entourage of the alaperusi and the musicians behind. This marks the final part of the function as pascoleros. A man, usually a soldier, is removing stones from the road where they will pass dancing.

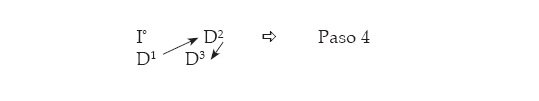

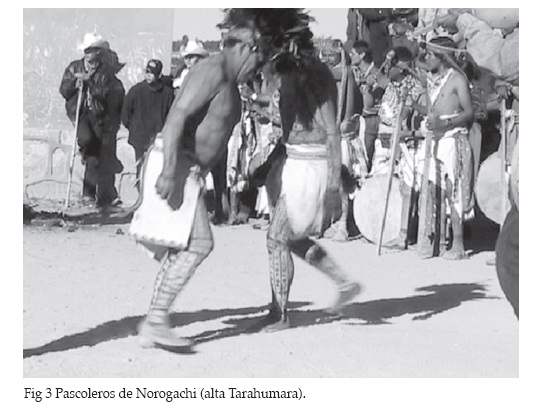

Steps and body position

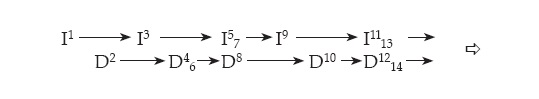

It is difficult to find fixed patterns of steps and movements, given that everyone has their own way of dancing, but thru the observations made, we can

highlight some constants.

The legs are bend all the time and are carried back by lifting the foot a lot with exaggerated movements. It supports the whole sole with normal step and redoubles. Arms are falling on both sides, with hands that sway back and forth, and body leaning slightly forward.

The shift occurs with little jumps; they stand behind their feet and bend their legs, with a slight support on the toe.

Semi-support a few times on the heel and some other times on the toe. When the semi-support goes for of before of another foot it is done by the heel, and if it goes behind it relies with the toe. Front semi-support on the heel, involves stretching the leg and flex the supporting one, creating a little jump. Semi-support in front of the heel, involves stretching the leg and flexing the one that is use as support, changing foot causes an immediate jump. The forward movement is done with little jumps, from one to the other side, sometimes with synchrony and sometimes changing the step. The supports and semi-supports are done sometimes very strong and some other times very softly. The eldest dancer goes always at the front and decides the step and direction. The rhythm and movements are very fast. Each dance consists of three short pieces that last from one to three minutes.

Dancers go with semi-support on toe or heel, and supporting sole on the same footing. If the front dancer is semi-supporting with heel, the next one will use the toe, in order to switch the motion. Sometimes he makes a sharp 90 degrees turn of the torso to one side. The movements are done with this step in all directions: forward, backward, in a circle, and so on. The leading dancer always has the feet and hands painted in black (female principle), the next one in red (male principle). The dance starts walking in circle with normal and slow step.

Paralenguage: facial expression, gestures, proxemics.

Placed one after the other and approximately 50 cm of apart, the one of behind imitates as far as possible the movements and displacements of the pascola leading the initiative. In many moments, the pascoleros couple will dance in unison: both on one side and performing the same steps at the same time. Some other times they dance with a contrast: One on each side with different steps, but always one after another and following the same trajectory. They dance very concentrated and focus the look directly to the ground, with a serious and serene expression.

Clothing and ornaments:

Zapeta (textile loincloth) and white skirt on top covering up the back of the knee, open in front and held with a belt. Bundle of metal bells; fasten to the waist and falling behind down to the height of the buttocks. Headdress of turkey feathers. Collera (ribbon around the head) stamped tissue below the headdress. The red and black paint covers the whole body: face, trunk, legs, feet (red) and hands (black). The feet are bare.

Musical accompaniment

Two musicians: a violin and a drum played with two sticks.

Environment

Easter Atmosphere, which means much public with high expectation in all places where the pascoleros perform, including the private act of the body painting and dancing inside the house of alapérusi. The tesgüino (Traditional corn beer) accompanies all times.

Towards the search of meaning. Between the ground and the sky

As the forms used in the pascol danced in the low Tarahumara and Norogachi, a community of the high Tarahumara are different, so does the role and significance of the respective choreographic structures. Based on data obtained during the field work -where we found that native versions on the meanings are not explicit and with few references found in ethnographical literature, which limits the contrast of our arguments- some possible lines of reflection and interpretation are offered to facilitate a better understanding of these cultural events, the inescapable task of searching for meaning.

Beginning with the pascol of low Tarahumara and their diversity, the first thing that stands out is the varied contexts in which it is put on stage. The pascol in the canyon is commonly use in any festive event: Christmas, Easter, saints and the patron festivals, national holidays, community events, weddings and so on. Any time of year is conducive to dance pascol, because ultimately, this is a joyful and fun dance, useful to encourage the attendees and in which it is allowed that anyone, man or woman, regardless of age, joins the group of dancers, forming long lines or wide circles. The pascol or pascola leads the active participation of those attending a party or events, which all share a common practice that generates a sense of unity.

In the dance structure, they all go together, one after another at a distance of barely half a meter, while maintaining a line with the pascolero at the start of the line. In the mixed groups, pascolero is usually a man and with his command stick, as a symbol of authority, leads the development of the dance which usually is followed by the rest of group. First the men and boys, and then the women and girls of various ages that close the group. Draws attention in this order the separation of men and women, who ordinarily do not mix; The woman who joins the dance in motion makes it placed as the last of the row, while the man who joins does so behind the last man but ahead of the first woman, although this is not a fixed rule. This provision of the men separated from women and ahead of them is very normal in different orders of daily life, and reflects a way of understanding social relations and the relative position that each one occupies because of the genre. However, the position of pascolero is not denied to women, who also wears the chayéhuares at the ankles and takes the initiative of inviting to dance pascol behind her to men and women. Thereby the women can dance pascol forming independent groups from that of the men, in the same group as them but behind or either mingled. (a man, followed by two women, followed by a man, followed by another woman and so on). All of which makes us see the flexibility of the norm in this style of dance and, therefore, social norms, as well as the woman who possesses the ability to make decisions themselves and get involved in social life regardless of the male. A remarkable fact in the choreography interpreted by pascoleros and only for them, not by the group of companions, is the variety of forms used and that, as well as in musical sounds that are associated with different animals or created situations related with the daily life in contact with nature.

The pascolero emulates the elements of nature with which he is familiar, reproduces passages of the life of the animals in cheerful tone, as a tribute to the environment and to the beings that inhabit it and with whom he wants to have a harmonious relation, the audience highly values the verisimilitude and good execution by the pascolero.

The rest of persons who accompany the dancer, on not having the practice and the knowledge of this one, follow all behind in a row, marking the step and trying to adopt as best possible the same body position. There is no difference between men and women, all doing the same thing with more or less style, further affirming the spirit of the group, an egalitarianism of the Rarámuri own life, regardless of the gender. On the other hand, the type of semi wretched step, and especially the one that produces the pascolero – with continuous rolls and dry and strong hits on the floor, with bare feet-, makes us see the attachment to the land they tread on, the confirmation on the territory and the hope that it will produce the expected harvest.

This so peculiar gesture characterizes pascol dance. In addition, the meaning that we attribute to it is situated in tuning in with the sense that some rarámuris give to this type of dance: to favor soil fertility in a broad sense that goes beyond the mere achievement of a good harvest, because agriculture is more valuable in the mountains than in the canyon. The imitation of the animals makes us see, besides this fact, as we indicate before, a singing and honoring to beings of the nature with which the pascol shares the existence.

The chayéhuares (ribbons with butterfly blossoms fulfilled with seeds) that they wear attached to the ankles evoke the idea of “transformation” or metamorphosis, of change because it is the leaving place of that animal. This symbolism, coupled with the fact that the seed makes the cocoon rattle, is of interest to believe that the intention is to transform the seeds in fruit, once germinated in the ground that they stamp so insistent.

With regard to pascol of Norogachi, the context in which it is performed and symbols with which it is linked explicitly tells of a dance announcer of a momentous event, as is the resurrection of Jesus Christ and the salvation of humanity through the victory of good over evil, hoping the coming of a better world. This is the interpretation heard of the missionaries, as well as the Rarámuris attached to them.

The pascoleros and their group marked by a cross representing the Christian community, come alone to church and out of it cheerful and triumphant; the pascoleros, along with the alapérusi and soldiers, lynch and burn a Judas surrounded by laughs, jokes and the shouting of the participants.

There is no doubt that for the church and its parishioners that is the precise meaning of pascol and the critical role of the pascoleros, and this will be for them if they believe, according to the principle of “whether a situation is experienced as real, is real in their consequences. ” However, this is not the only reality or meaning that we can find. From one hand, we have that while pascol and pascoleros represent a symbol of victory, the triumph of good over evil, it is not clear to everyone that it necessarily connects with biblical passages, even if the context suggests. Rather, we believe that the pascoleros and the pascol dance finalize the conflict, the struggle between good and evil lived during the Holy Week. This Certifying the victory of good and the defeat of evil14, but not so much an asset associated with Jesus as with the Rarámuris themselves, represented by the alapérusi and soldiers. Without forgetting that there is a Rarámuri cross placed in the house of the alapérusi, where the pascoleros are painted and where the retinue leaves marked with the cross on the forehead, with their own cross. The evil, for its part, has Judas as the highest expression, but more than the enemy of Jesus, for the forms used is a reflection of the way to be chabochi (white man), represents the vices of the chabochis, the evil that for them is part of their specific experience and they seek to get rid off. Therefore, the hope of salvation is therefore the yearning of the Rarámuri people to dispose the bad chabochi influence, its oppression and domination.

All this happens within a very well cared representation, where one can see the implicit presence of Onorúame. Without being named, we think it is in the collective Rarámuri conscience. In the alapérusi’s house, the private space where he has nailed a cross that evokes their presence, and around which the pascoleros abandon its role at the end of the acts, and in the same tesgüino (water of God, Onorúame) that is being served since the start of the pascoleros painting on Friday night. The power of the church, its authority on space and time at which this event live on the temple and the Holy Week, does not prevent that Rarámuris not interpret the tragedy in their own way, using their own forms of expression Or to abandon their traditional thinking, which does not cease to be present in the search for meaning.

Placing again in this quest for meaning for the proper natives, it is necessary to ask, what does the pascolero painting mean, his attire? What meanings emerged from the pascol dance, of the movements it produces? For some the first dilemma is easily resolved and point out that the person with the painting becomes the angel announcer, a pascolero. The scholars can see in the forms of painting the picture of the old armor of the Spanish soldiers, and even those who used to dress certain warriors angels and archangels (as the archangel Michael) in the paintings. This is a witty idea and loaded with no little reason, since it makes us think that perhaps the painting of pascolero is based and influenced by those images that came from abroad, which could be a likely scenario.

It is also worth asking why the naked body is painted and did not dress according to what they want to represent. The answer is found in the custom. For the different meanings that can be attributed to these characters and dance to interpret, the players have to show the most natural way possible, presenting their naked bodies unequivocally, and using on them the painting as a means to convey ideas and transform the people in what they represent.

For the process, the transformation in pascolero requires passing through a stage of purification, in which the body is washed with lukewarm water and is painted in white to better highlight the colors red and black that will cover it completely. Apart from the lines, points and crosses, forms used with the painting and that well that could inspire by an armor – though such an idea does not fit in the native thought, for them it only is painting a pascolero in the traditional form-, the attention is called powerfully to the alternation of the colors used in both bodies.

It is used red and black interspersed throughout the body surface, and as a differentiating feature, one pascolero paint the back of his hands and feet in black, while another one makes it red. Bearing in mind that in the rarámuri world red represents the male principle, day and light, while the black is for the female principle, night and darkness, the play of colors used represent the complementarities of the two principles in the person’s life, both of which are impregnated by them. However, while representing a male (With his hands and feet red) and the other represents the female (with his hands and feet black), it is about representation, and although both are men as pascoleros they reflect this structural duality.

The belt of metallic sleigh-bells possesses to our judgment an eminently material and practical sense, in the measure that constitutes an effective way of being made notice during the dance by the sound that it produces. The headdress of turkey feathers, for its part, has a more symbolic meaning in all that it equalizes them with the group of soldiers (defenders of the good) who also take it, and contributes to give them a much war likely appearance, since apparently such feathers were used in the war dances of the past. The soldiers (rarámuri captains) guard all the time the pascoleros and clean from stones the space where they will dance, unmistakable signs that they belong to the same side.

On the other hand, from the symbolic point of view should be considered the order that the pascoleros follow and the dynamics of their choreographed movements: black foot go in front of the red foot red following the first ones, and thus the male principle follows the female principle, who is leading the movements. This coupled with the manner of movements – in which many see a representation of certain animals being in season15, especially deer, – makes us suspect that this dance could express its origin in courtship or sexual flirtation of two animals, presumably deer, for the little jumps that are continuously done.

Two animals (female and male), that are pursuing a very short distance, making winding paths and circles, as a symbol of life that revolves on its own. Is entering the spring, it is time to procreate and, therefore, this dance play a feature in the nature and constitutes a sign of fertility, commensurate with the time that they must live within the annual cycle.

This way then, Norogachi’s pascol does not possess an unambiguous and unique meaning; far from it, we think this re-adapted dance says much of the rarámuri world vision. And though because of its festive context, it has interpretations that flirt with the Annunciation of the best world after the victory of the good (for some personified in Jesus and for others in rarámuri) on the evil (for some Judas and for others chabochi). In agreement with the context marked by the ecological calendar, the idea of the fertility and reproduction of the life also it is situated present and is also significant.

Bibliography

Bennett, W. C. y Zingg, R. M., Los tarahumaras, una tribu india del norte de México, México, Instituto Nacional Indigenista, 1978 [1935].

Breen Murray, W., “A Tarahumara Body-Painting Ritual”, Chihuahua, Escuela Nacional de Antropología e Historia, Fondo Smithsoniano, exp. 258, caja 9, 1981.

Gardea, J. y Chávez, M., Kite amachiala kiya nirúami (Nuestros saberes antiguos), Chuihuahua, Gobierno del Estado, 1998.

González Rodríguez, L., Tarahumaras. La sierra y el hombre, Chihuahua, Camino, 1994.

“Notas demográficas”, en Boletín Trimestral del Consejo Estatal de Población, segunda época, año V, núm. 17, enero-marzo, 2003.

Ocampo, M., Historia de la misión tarahumara (1900-1950), México, JUS, 1966 [1950].

Olmos, M., El sabio de la fiesta. Música y mitología en la región cahita-tarahumara, México, INAH, 1998.

Velasco, P. de, Danzar o morir. Religión y resistencia a la dominación en la cultura tarahumara, México, Centro de Reflexión Teológica, 1987.

Wheeeler R., La vida ante los ojos de un rarámuri, Chihuahua, Agata, 1992.

Author: Ángel Acuña Delgado, Universidad de Granada, España

- See Demographic notes “Notas demográficas”, in Boletín Trimestral del Consejo Estatal de Población, segunda época, year V, nbr. 17, jan-march, 2003. [↩]

- P. de Velasco, Danzar o morir. Religión y resistencia a la dominación en la cultura Tarahumara, 1987, 211 [↩]

- L. González Rodríguez, Tarahumaras. La sierra y el hombre. 1994, 21. [↩]

- W.C. Bennett and R.M. Zingg, Los Tarahumaras, una tribu india del norte de México, 1978 [1935], 483. [↩]

- W. Breen Murray, “A Tarahumara Body-Painting Ritual”, 1981, 21. [↩]

- According to Rodríguez (see M. Olmos, El sabio de la fiesta. Música y mitología en la región cahita-tarahumara, 1998, 72), between the Cahitas the word pascola refers literally to the “Wiseman of the Festivity”. Pascola comes from the Yaqui-Mayo word “pahko” (party) and “o’ ola” (old), which can be interpreted as the most ancient, old or experienced in the festivity. [↩]

- ENAH Chihuahua, CCIT, leg. 51, exp. 6, box 203, fols. 3 and 4 [↩]

- See J. Gardea and M. Chávez, Kite amachiala kiya nirúami (nuestros saberes antiguos), 1988, 97. [↩]

- Even when pascoleros usually use tapes with butterfly cocoons tied to the ankles, Ocampo referrers to them as snakes rattles elements to transform their feet into drums “in the dance of pascola, specialty of Cerocahui, both feet near the ankle are adorned with string of bells that they pull out of the vipers. See M. Ocampo, Historia de la misión Tarahumara (1900-1950), 1966, 54. [↩]

- R. Wheeler, La vida ante los ojos de un rarámuri, 1992, 149. [↩]

- Interview to C.V., April 12, 2003. [↩]

- Interview to J.G., April 10, 2003. [↩]

- The data presented here has been collected among the communities of Cerocahui, Guagueibo, Wapalaina, Guadalupe Coronado, San Alonso y Huetosácachi. [↩]

- Olmos notices that the atmosphere is of happiness and celebration on the new social order having be restored at the end of the holy week; see M. Olmos Op. Cit 78. [↩]

- See P. de Velasco, Op. Cit., 211. [↩]