If you ask a Maya1 of Xohuayán2 what shape has the land and how the soil in which they live is, will not say with exclamations that it is the best, the incomparable one, which goes in the thought. Neither will he argue that it is, or it has, the form of a crocodile or of an iguana, which is as like his forbears were identifying it, according to Thompson’s opinion.3 He will say simply that it is their very yok ‘ol b ‘ka, or that is the heart of everything4, in the center the world, and which has three parts: muuñal (heaven above),5 Ka’b (land here) and Hell (down), plus that it is square because so decided God. On this basis, they add, so also his home, his people and his cornfield have four sides equal in size, “none bigger than the other, so that their owners are not mad”.6

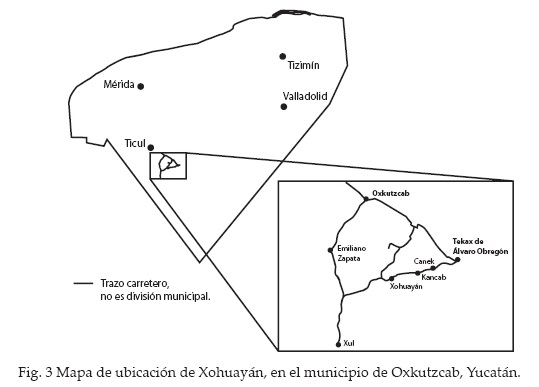

This is what it is worth, plus his being Maya. Otherwise, it can change the belonging to a municipality, to a state or a country. That comes from the very beginning of things, since the launch of the world, since God created, distributed and measured it, they say.7 On the other hand, the second thing not, since it is a thing of tastes or displeasures, of political or economic interests, as Mario May Chan affirms: “before we were getting about ourselves with Tekax, and already not. Was saying my grandfather Luciano that the authority always changes, because of it equal it was possible to be with Tekax, Oxkutzcab or Akil; but the land not. Land is always with its four sides, since the former parents were living”.8 This sense of belonging to a certain land and this meaning of the former parents are the point of union, the direct link that they have with their past, same that allows them to give coherence to their being and belonging in live.

With a supposition like that, it is not strange at all that they define themselves as Mayan or Xohuaimiloob, and that have great difficulty explaining why they are also Yucatecos and Mexicans. They also emphatically reject the fact to be called Indians, concept they consider demeaning in non-racial, but cultural terms. They are not because they are macehualoob, work and live off the land, do not walk naked and have no feathers on the head.9

The Horizontal World

The xohuaimi relate that each of the sides mentioned above have a guardian and special characteristics. They only know one guardian name, Yumtzil (God, praiseworthy Lord), therefore they use it in general and, just as their ancestors did, they continue to associate them with a specific color: red to the east (lakin), black to the west (chikin), white to the north (xaman), and yellow to the south (nohol). These guardians protect the place that corresponds to them making it agreeable to the man, as long as man invokes to his help and protection by means of the ritual.

This connection marks the difference between one Yumtzil and another. As they have well-defined territories, also require special offerings. The forgetfulness that is made of one of them will not only cause the indifference and neglect, but their anger, their attack and exemplary punishment. They are, undoubtedly willing and volatile, capable of all good, but also of any evil. Nobody puts in interdiction this, but as they are conceived more in terms of magnificence always strive to give notice when they are being breached. Don Mario May exemplifies this, in his own words:

Tengo mi rancho allá en mi propiedad, con mis gallinas y mis pavos. Sólo así se hace algo, pues acá las perjudica la peste. Un día vimos doña Toya y yo que faltaban dos gallinas, y buscamos qué era. Una serpiente dejó su marca, y me quedé para verla. Llegó en la noche y la maté. Luego vino otra, y le hice siempre lo mismo.

Otro día en que fui a mi rancho a dar agua, que me encuentro un señor ahí sentado en el camino. Blanca su ropa. Buenos días –le dije-. Buenos días, me contestó. Le pregunté que hacía, y me dijo que sólo estaba ahí para buscar sus animalitos. Que le faltaban dos, que si no sabía nada, que por qué los había matado, que si me habían hecho algo. Yo le platiqué todo, verdad, Jesús, verdad, y me aseguró que les iba a preguntar. Si era cierto, ya no habría daño en mi rancho, ya no iban a regresar.

Al otro día me lo volví a encontrar. Me dijo que no tenía, y que ya las había castigado, pero que yo también tenía falla. ¿Por qué no pediste mi permiso para trabajar aquí? ¿Por qué no pediste mi permiso para matar a mis animalitos? Entendí todo. No entregué saka’ y ya de eso vino la problema. Así lo platicaba mi abuelo, que no es bueno olvidarse de los yumtziles, de ninguno, pues es cosa sagrada. Y si se entrega nueve veces en la noche es mejor. En el día deben ser trece, pero no sé por qué. Eso decía mi señor Luciano.

Pero ya cumplí y ahí está mi trabajo.10

According to don Chavo, the ah men from Oxkutzcab, there is a fifth transcendent color for the Mayan people: the green, of equal way with his specific protector, who corresponds to what is in the center, which binds to the surrounding four-sided earth surface.11 However, in Xohuayan nobody assured to know something about it, not even don Crescencio Polanco, another ah men12 as effective and strong that their enemies never defeated him, only by the yumtziloob because they liked very much his singing said Rufino Cauich Ku, his son of rearing and education, not of progeny.13

The only exception in terms of knowledge of the name of the guardian is T’uup Balam, the smaller of the balamoob possession of which is the east, the place of light and energy. By occupying the place where the sun rises, and being the younger brother, the supporter of the burden of the earth, according to the Chilam Balam of Mani14, his importance is unquestionable; he is sacred, according to the old Mayas from Yucatan. The youngest child is the most important one, the smallest, the t’uup, as this is who defines the system of inheritance. Male obviously. On the other hand, the guard and, by extension, the divine side that causes more anxiety and fear is the south, which they consider to be the least propitious to their live for coming from him, and from there the bad winds.15

It is worth noting here that if the protective side of this is a Balam (Jaguar), those of the other gods must be equally jaguars, as continues to believe in neighboring villages as Kandumbalam. However, despite the clarity of these concepts about the world we are moving in the community apparently there is no longer a creation myth to justify them, nor to explain them.

The Vertical world

In relation to these three levels, they say that the land is in the middle; above, in the top level, remains the muuñal; and below, in the lower level, one finds the hell. There is no longer the belief that they are prepared in thirteen or nine floors or regions, respectively, but in its expression continues this ritual, via the ceremony Ch’a Chaac in the first case, and by the Hetz-lu’um in the second. In the first case, they deliver to the lords of the sky, for each cardinal point, loaves of bread of twelve layers divided into two sections, plus a pan w’eech (armadillo) that crowns the offering. For the second one, they offer to the guardians of hell nine cocoa beans and nine chilies, grouped in pairs, for each cardinal point, acting the remaining cocoa as a teacher of others.

In both processes the conformation in pairs allows me to suppose that the former Maya of the region were arranging the floors of heaven and of the underworld not in a strictly vertical sense, but rather staggered, forming a pyramid in both planes with the land as common base. Therefore, every morning the sun crosses the ascending steps of the east until it reaches the seventh floor, which is the zenith; for later in the afternoon, descend the other six in the west and spend the night journey. Than continue down the four steps of the east, to finally bring back the day.16

The three levels of the world have a close communication with each other, and the balance between them depends in the very existence of the gods as of men. For the same reason no man, no woman can or should keep a passive attitude on the site in which they live, because if they do not meet their guardians needs, they cannot maintain the proper functioning of the world, which inevitably involve the destruction of all. This idea is reminiscent of the belief of the pre-Columbian Mayans that gods’ discontent could generate not only divine punishment for human beings, but also the confrontation between the gods from high and low, and if the world’s underground wins, the consequences would be terrible because the sky would collapse and the earth would be devastated. That says the Chilam Balam of Chumayel.17

The order of the world

To avoid the cosmic disarray, the human act is aimed to offer up their divine beings, that inhabit it all, a fundamental gift: work, same as in the case of men has its primary expression in the cornfield, and in the case of women in the three stone stove, in turn center of the kitchen and the family.

The stove and the cornfield are complementary, not contradictory as cultural value, as they summarize the basic survival of both human and divine: the food. With it, there is order, there is creation, there is regeneration, and therefore are scale reproductions of the worldwide. The stove in vertical since there is preserved the vital fire that holds together the three levels of the world, symbolized by a stone each; as commented the ah-men Pablo Dominguez, women help the sun to be reborn, to regenerate every day after his trip through the dark18. In addition, the cornfield in horizontal, symbolized by a stone by side, the so-called Mojonera, that is the breadwinner and home guard of things. Logically, the essence of men and women xohuaimi, its primary energy, is present in them since the beginning of life, because they hold the umbilical cord of their sex. This is not futile, as demonstrated by the entrenched belief that human beings are connected with it to their gods, no sense of dependence but of everyday living. Moreover, if the ancient Mayans said that the cordon was important because it connects the celestial deities with the noble land19, the modern Maya of Xohuayan say that is something wonderful and amazing how God mark some children with a prenatal umbilical knot.20

If you are looking for a reference to the importance of food in the testimony of past pre-Columbian Maya, one of the best examples is offered in “El Lenguaje de Zuyua”. Where not in vain a symbolic part of the whole corpus is: to produce to eat, seek to eat, make and give to eat, because this provides temperance, happiness and true word. Whoever fails to meet this basic obligation is sentenced to suffer terrible punishment. As it Says at the end of Part I:

Cuando termine el poder del 3 Ahau Katun se aprehenderán los Batabes, los-del-hacha, de los pueblos, que carezcan de entendimiento, por eso se les aprehende; porque no dieron de comer a los Halach Uiniques cuando éstos les pidieron su comida con acertijos; por eso son ahorcados y por eso les son cortadas las puntas de las lenguas y por eso les son arrancados los ojos en el tiempo en que termina el poder del katún.21

As the stove and the cornfield, men and women are also are complementary to their gods. They know that the Hahal God created them, the very certain, real and big God; and that owe respect to him and to his assistants; but also they have full conscience of which role is fundamental for the existence of the world, which implies daily participation in the search of a balance among the diverse forces that compose it. This need to act in the sense showed by “the owner of the things” is the destiny, same that justifies itself especially in the ritual of the hetz mek.

Ceremonial magic propitiatory, the hetz mek is performed on girls at three months and in boys at four months, in clear allusion to the role they should play in the future of their community. To keep the vital fire of the stove and to prepare the food, in the first case; and to produce in the cornfield enough for the subsistence and good functioning of the family, in the second one.

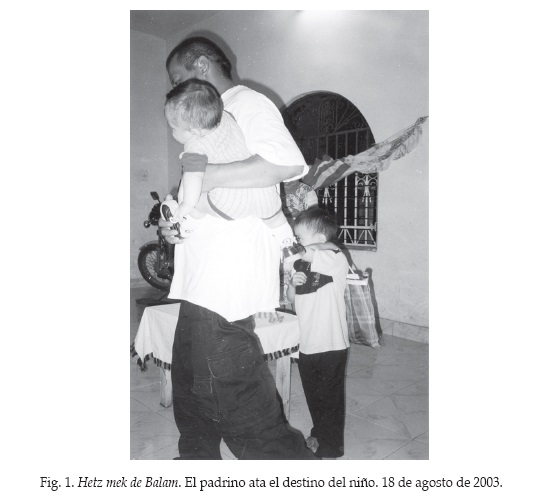

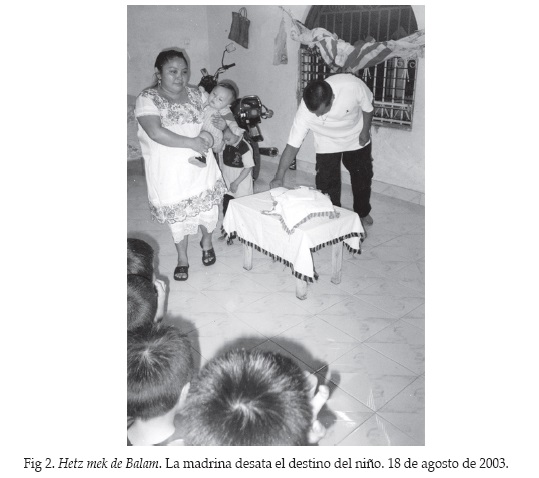

The hetz mek translates literally into English as “astride,” but symbolically it defines as the tie and untie of fate, which understands very well if one observes carefully the tying that make the legs of the infant around the person who carries him/her.22

In front of a table with several food prepared with egg, pumpkin seeds and corn, the godfather carries the baby in his left side and ties the destiny with nine laps around the table, always to his right for being the side of the Sun and to whom he is related. A small bay accompanies the godfather, who carries a haversack with useful objects for the future life of the godson, delivering the baby one on every round, previous explanation of the use that the child will give to it, as well as the respect that the baby must demonstrate with everything that surrounds him or her. To avoid possible misunderstanding as to the number of turns, a person named to that effect should put on the table a grain of corn for each turn.

When the godfather concludes, the godmother takes the baby in hetz mek on her right side, and turning in the opposite direction unties the destiny with equal number of rounds that the godfather, also giving to the child all the objects of the haversack. For girls: dough, thread, cloth, needle, some tool of the kitchen. For boys: machete, “coa”, corn, “jícara”, “posol”, among other things. For the last twenty years, include also a pencil, a notebook and a book.23 It is important to clarify that to tie and untie the destiny are not contradictory elements. God provides this, but nobody knows what kind of “luck” is given to individuals when they are born, whether fortunate or unfortunate. Tying the fate involves trying to influence the “lucky” to what effect, socially speaking; it is to say, in both cases is determined towards the collective interest of survival. Unleash the destiny is not to oppose it, but to deliver infants freedom, opportunity and decision to continue or not in future the path marked by the people and by God. Everyone will answer for the consequences of their decision, without a doubt, and it is not the slightest the deterioration of their identity.

After the feats, the proud parents can now point out that if their baby has a place and responsibility in the world and, therefore, will not walk around like lost, not knowing what to do. Moreover, how will they not be happy if the knot always unifies and binds both in life as in death, as Teresa Rodhe affirms24.

With this ceremony starts at the community also a social commitment, a contract for acceptance of traditions and habits that leads logically to the survival of the people. From that time, infants begin their learning into the future: the boy has to be like the sun, giver of energy, force and order, maintaining and supporting its creation. The girl should be like the moon, Mom moon, reproductive, regenerative, fertile safeguarding the heat wave and family unity. The confluence of the two allows for a lasting existence.

Once again, “El Lenguaje de Zuyua” gives us an excellent version of the integration that should always exist between men and women, at all times, whether they were for government positions in the community, whether the governing only their houses. Relates the following proof number four:

El cuarto acertijo que se les hace es que vayan a sus hogares diciéndoles: “Hijos míos, cuando vengáis a verme, ha de ser precisamente cuando el Sol está en el medio del cielo, seréis dos y vendréis muy juntos vosotros, muchachos, cuando lleguéis aquí, vuestro perro doméstico ha de venir tras de vosotros y que traiga cogida con sus dientes el alma de Cilich Colel, Sagrada-Señora, cuando vengáis. Habla es de Zuyua”. Los dos muchachos de que se les habla que han de venir juntos justamente en el medio día, es él mismo cuando venga pisando su sombra, y el perro que se pide que venga con ellos es su propia esposa, y el alma de Cilich Colel, Sagrada-Señora, son las grandes candelas, hachas de cera. Tal es el habla de Zuyua.25

Just as the sun and moon are never contrary, men and women cannot be, because they only integrate one another. However, this integration, this close relationship is not tantamount to equality, nor is there between the former. Similarly, to what happens in the sky where the sun is over and above the moon in size and light in the land dominates the male principle to female. Although the two governing the world: the sun and man as parents, giving strength and vital heat and the woman and the moon as mothers filling it with goodness, fertility and regeneration.

On this basis, farmers of Xoahuayan are still certain of the lunar fertility. The waning phase of the moon or the so-called old moon is considered most appropriate in this regard. It is only when this celestial body is in the east, the side of the world with more light and power by being the father sun, but also because it gives the bushes a chance to grow with the moon, taking advantage of all their nutrients. If someone dares to sow in the days of new moon, or full moon, knows in advance that has great risk of getting little or no harvest, because his cornfield will not have any help for its development.

Al sembrar con la luna, cuando entregas el maíz a la tierra ésta nos responde, no nos abandona. Y si cumples tu promesa de pedirle su permiso a los guardianes de todo, a los yumtziloob, para que faciliten la tumba y alejen los peligros que nos dan las serpientes, los alacranes y los vientos malos del sur, y si le pides a nuestro padre Chaac que le eche al agua, y si haces Ch’a Chaac para que la lluvia sea abundante, y luego no te olvidas de la primicia y les das a los señores de las cosas y al Hahal Dios su comida, entonces no tienes por qué preocuparte, porque ya lograste tu cosecha, y ésa es la vida, y qué más.26

This is what Juan Gualberto Xool Domínguez says, who also assures that Hahal God is the owner of everything, because he is the truth, the real and the great God.27 In sum, and in line with what the pre-Columbian Mayans thought, according to the studies of Mercedes de la Garza and other specialists;28 the xohuaimi know that the world, their world, depends on themselves, always to the extent that, although everything is written by God, this never would contravene the welfare of His creation, unless we humans forget our commitment to Him and make things inconvenient and not useful for the people. Don Prudencio May explains it this way:

Dios manda las cosas. Unas buenas y otras malas. Así es. Pero no dice su orden luego. No dice esto te toca a ti, y esto a ti. Primero ve tu forma, tu respeto, te pone pruebas. Si no eres gran pecador, no te pasa nada, tu suerte es buena, con enfermedades sencillas, con buena milpa, con buena miel. Los yumtziles no te maltratan. Pero si tu falta es grande, ahí está el mal. Ya no te levantas. Tal vez de casualidad con el ah men, pero de casualidad. No es seguro. Tú sabes por qué pasan esas cosas.29

The space in the myth

Some of the aforementioned rites, including the Ch’a Chaac (request for rain) and W’a-kool-ji (the tortilla, bread from the cornfield), and others like W’a-ji-ch’e ‘In (the tortilla, bread from the dwell), and hetz-lu’um (the burden of the earth: the house), are for the Maya xohuaimi clear proof of the relationship and communication between the guards of the three planes of the world and their respective sides. However, to justify such relations in the myth becomes more complicated. In that sense, the two stories below are the only ones I could collect. Don Victoriano Chan May, explained one to me:

Decían los antiguos que hace muchos años unos animalitos que son muy malos y burladores, los sirw’oi, que viven en agujeros que hacen entre la tierra y el tronco de los árboles, vieron que los chaacoob estaban trabajando pero no con muchas ganas, y empezaron a mover la cabeza y a burlarse de ellos enseñándoles los dientes. Con la burla, los chaacoob se enojaron y enviaron a sus rayos con gran fuerza para matarlos. Eso ayudó para que hubiera más agua y más cosecha.

Nosotros sabemos que los sirw’oi también ayudan a la tierra, y por eso cuando nos enojamos también nos burlamos igual que ellos, enseñándole los dientes a la otra persona.30

The meaning of this story is obvious. The land needed vitality and power from the high; but the heavenly gods for some reason refused to comply with its obligation. The lords of the underworld intervened and via the representation of the sirw’oi demanded the chaacoobs to send the needed rain and in exchange, they offered that animal sacrifice. The thunder, a symbol of power and authority, sealed the commitment to open the worlds and exchange gifts.

The other is a prophetical myth. Speaks about the fear that every rural village has before the possible lack of water for the subsistence of the living, and the fear moves everything sacred, moves the entire cosmos. And it speaks about the dangers that the decomposition of the world carries; but speaks, especially, about the possibility of regeneration of the man with his ethical duty: Do not be a threat to the survival of the genre. This is the testimony of Juan Gualberto Xool Dominguez, Couoh Moses Chan and Chan Baltasar Cahuich. It says that in The Cenote of Maní lives a feathered serpent that besides taking care of the water is responsible for monitoring what is happening in the world. To do its job well, the feathered snake goes up to heaven with the help of a rope or living string (cuxan sum) that tends among the cenote and the church of this village, and from there notices everything, although it does not help anyone, apparently angry because the Mayans are macehualoob from strangers. However, the day will come when the sky will stop, the clouds will not move and a great drought will cover the land. At that time, the serpent will help calm the thirst of his people, but it will require that they deliver a child in sacrifice. Moreover, this will not end until it reaches the man chosen to accompany its travels in the cuxan sum, which is responsible for freeing the Maya and re-establish order in the world, with the sky moving again.31

The version is significant, and certainly has a relation with how the precolumbian Mayas interpreted the world, as reflected in the books of Chilam Balam: relations and clashes of the guards or lords of the underworld and the heaven, the destruction of the world, punishment to the usurpers, the thieves, to the false and irresponsible, drought, famine and struggles over water. And with regeneration, restoration of the world and of man, with movement of the sky, the sun and the earth. For example, at the cuceb or prophetic Wheel of the year 12 kan, a Katun 5 Ahau, reads:

12 Kan, Piedra-preciosa, en Uno Poop, Estera. En el decimotercero año tun será el día que diga su palabra el Sol, cuando se hablen mutuamente los zopilotes; los hijos del día a los hijos de la noche, en el cielo y en la tierra; será en este decimotercero año tun cuando ardan los cielos, y la tierra tenga fin dela codicia. Así ha de suceder por el exceso de soles: y vendrán los ruegos a Hunab Ku, Deidad-única, para que su majestad tenga compasión.

Siete serán los años de sequía: estallarán entonces las lajas, arderán los nidos de las aves arriba, arderá la savia del zacatal en la llanura y en los barrancos de la sierra. Entonces volverán a la gruta y al pozo a tomar su comida de espanto, y entonces rogarán a los Ah Kines, Sacerdotes-del-culto-solar, que se ajusten la preciosa manta a la espalda, con el cinturón de trece nudos. Cuadrado será entonces el rostro del Ah Kin, Sacerdote-del-culto-solar, cuando en este katún entren de nuevo a su pozo, a su gruta, y hagan más intensas sus imploraciones en la gruta, a su pozo de nuevo y venga nueva sabiduría, nueva palabra. Así lo dijo el gran Chilam Balam, Brujo-intérprete.32

This relation is best understood by noting that Xohuyán is close to several of the sites from which some of the books mentioned come, and therefore shares without a doubt many of these cultural heritages. Tekax is located to 11 Km; Maní, to 30; Chumayel to 35, approximately; Teabo, a Little more than 30; and Oxkutzcab, the main town, to 18.

Hence, in the heart of Puuc are xohuaimi, facing many battles for “being there” and “doing”, offering their work to the gods, the lords of things, and avoid the world of the dead to install. This risk is present at all time, says the story of “The Lazy Daughter-in-law”: If some member of the couple does not stimulate other one to avoid the laziness, both pay the punishment, “since they are not alone, since they are a family to support and to support a house, and not let the souls to come to do it”33.

Conclusion

Much has been said about the pre-Columbian Mayas, belief that time is cyclical, and that therefore they had a dependent relationship with their deities to be repeated so eternal, sometimes fortunate, and sometimes unfortunate, according to the load that wore the gods.

With minor variations, this belief is still present in the “current” Maya and the case here studied proves it. However, that dependence is not to be thought in dramatic and inexorable terms, as human beings can choose their way forward according to their behavior. The bottom line is not to offend Hahal God, or put at risk the safety of the community, they argue.

That means keeping a very close relationship with the heart of everything, with the land that has three levels in the vertical, each defined by the four cardinal points. Based on that, they organize clearly their daily lives. The basic point of attachment, the three levels, corresponds to the woman, mistress of the dark and the unknown, and, as caretakers of the sacred fire, that gives warmth and food to the family. That is why her symbol and her destiny is the three-stone stove. In turn, corresponds to men the place of energy, under the tight control of the sun, and then there will produce what is necessary for the sustenance of his person and of the gods. If the man was made of corn, where he must act more, if not in the cornfield?

To determine a good performance during their life around the space that belongs to them according to gender, xohuayanos turn to, like all the Yucatecan Maya, the ceremony of Hetz mek, which has both religious and social implications.

That space is always divine, not only because the guardians of things inhabit it, but also because Hahal God created it; and in that sense human beings are due to integrate it with respect and harmony, and then do not go against its very essence, against his being. Therefore, it is necessary to request permission to be and act on it, in order to exert the necessary work for the maintenance of all, including the gods.

To the degree that humans do not forget to fulfill these essential duties and to propitiate life, are ensuring the existence, the way in the world. The ritual confirms it, both the individual one, and the group one. And the singing, and the poetry, celebrate it:

Estando bien con Hahal Dios,

Se canta como el pájaro carpintero;

Y si cnta la hermosa serrana,

Se olvidan, se olvidan las penas.34

Bibliography

Aguirre Beltrán, Gonzalo, Cuijla. Esbozo etnográfico de un pueblo negro, México, FCE (Obras de Antropología), 1974.

Anales de Antropología, México, Instituto de Investigaciones Antropológicas-UNAM, vol. XVII, II, 1980.

Álvarez, María Cristina, Textos coloniales del Libro de Chilam Balam de Chumayel y Textos glíficos del Códice de Dresde, México, Centro de Estudios Mayas-UNAM-(Cuaderno 10), 1974.

Arzápalo Marín, Ramón (coord.), Calepino de Motul. Diccionario maya-español, México, DGAPA-IIA-UNAM, 1995, 3 vols.

Barrera Vásquez, Alfredo (dir.), Diccionario maya. Maya-español, español-maya, México, Porrúa, 2001.

Campbell, Joseph, El héroe de las mil caras. Psicoanálisis del mito, México, FCE, 1984.

Coe, Michael D., Los mayas. Incógnitas y realidades, México, Diana, 1986.

Corcuera, Sonia, Entre gula y templanza. Un aspecto de la historia mexicana, México, FFyL-UNAM (Colegio de Historia, Opúsculos, Serie Investigación), 1981.

Dahlgren, Barbro (ed.), Historia de la religión en Mesoamérica y áreas afines. I Coloquio, México, IIA-UNAM (Serie Antropológica, 78), 1987.

Davies, Nigel, Sacrificios humanos. De la antigüedad a nuestros días, Barcelona, Grijalbo, 1983.

El Libro de los Libros de Chilam Balam, (trad., de Alfredo Barrera Vásquez y Silvia Rendón), México, FCE (Popular, 42), 1978.

El Libro del Consejo, trad. y notas de Georges Raynaud, J. M. González y Miguel Ángel Asturias, México, Coordinación de Humanidades-UNAM (Biblioteca del Estudiante Universitario, 1).

Eliade, Mircea, El mito del eterno retorno. Arquetipos y repetición, Madrid, Alianza Editorial/Emecé (El libro de bolsillo, 379), 1984.

Lo sagrado y lo profano, Barcelona, Labor (Punto Omega, 2), 1983.

Mito y realidad, Barcelona, Labor (Punto Omega, 25), 1983.

Escobar Rodhe, Teresa, “Los nudos: apuntes para una investigación iconográfica”, en Barbro Dahlgren (ed.), Historia de la Religión en Mesoamérica y áreas afines. I Coloquio, México, IIA-UNAM (Serie Antropológica, 78), 1987.

Garza, Mercedes de la, El universo sagrado de la serpiente entre los mayas, México, IIF-Centro de Estudios Mayas-UNAM, 1984.

Sueño y alucinación en el mundo náhuatl y maya, México, IIF-Centro de Estudios Mayas-UNAM, 1990.

Landa, fray Diego de, Relación de las cosas de Yucatán, México, Porrúa (Biblioteca Porrúa, 13), 1982.

León-Portilla, Miguel (coord.), Tiempo y realidad en el pensamiento maya, México, IIH-UNAM (Serie Culturas Mesoamericanas, 2), 1986.

López Austin, Alfredo, Cuerpo humano e ideología. La concepción de los antiguos nahuas, t. I, México, IIA/UNAM (Antropológica, 39), 1980.

Llanes Marín, Elmer, Los niños mayas de Yucatán, Mérida, Maldonado Editores, 1983.

Matos Moctezuma, Eduardo (pres.), Dioses del México antiguo, Barcelona, Océano/UNAM/El Equilibrista, 2003.

Mediz Bolio, Antonio, La tierra del faisán y del venado, México, SEP (Lecturas Mexicanas, segunda serie, 97), 1987.

Nájera Coronado, Martha Ilia, El don de la sangre en el equilibrio cósmico. El sacrificio y el autosacrificio sangriento entre los antiguos mayas, México, IIF-Centro de Estudios Mayas-UNAM, 1987.

Peniche Barrera, Roldán, Fantasmas mayas, México, Presencia Latinoamericana, 1982.

Sotelo Santos, Laura Elena, Las ideas cosmológicas mayas en el siglo XVI, México, IIF-Centro de Estudios Mayas-UNAM (Cuaderno 19), 1988.

Thompson, J. Eric S., Grandeza y decadencia de los mayas, México, FCE, 1984.

____________, Historia y religión de los mayas, México, Siglo XXI (América Nuestra,

7), 1982.

Villa Rojas, Alfonso, Estudios etnológicos. Los mayas, México, IIA-UNAM (Antropológica, 38), 1985.

____________, “La imagen del cuerpo humano según los mayas de Yucatán”, en Anales de Antropología, México, IIA-UNAM, vol. XVII, 1980, t. II, pp. 31-46.

____________, “Los conceptos de espacio y tiempo entre los grupos mayances contemporáneos”, en Miguel León-Portilla (coord.), Tiempo y realidad en el pensamiento maya, México, IIH-UNAM (Culturas Mesoamericanas, 2), 1986.

Author: Jesús Guzmán Urióstegui

- The first version of this work was presented at the First Symposium of Regional Studies “Land ownership in the regional shaping. Past and present”, held in the city of Queretaro by the Universidad Autónoma de Querétaro, the Instituto Tecnológico de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey-Campus Toluca, the Court of the State of Querétaro and the Centro INAH-Querétaro, from June 1 to 3 2005. For this, I appreciate the comments and suggestions from the consultants. [↩]

- Xohuayan currently has around one thousand inhabitants. It belongs to the municipality of Oxkutzcab, which is located in the southwest part of the state, between 20° 00 ‘-20° 30′ north latitude and 89° 00’-90º 00 ‘latitude west. This article is part of a larger investigation that is the starting point to my arrival in Yucatan in October 1987, to make my social service, and it ended up being an enjoyable stay for several years, which run until 1992, adding some short trips after that year. During that time I noticed, talk, inquired, I was involved, motivated myself and motivated me to write about the life of the community. Thanks to all the xohuaimi for that special distinction, especially to Mario May Chan, Florentino Domínguez (don Toba), Juan Gualberto Xool Domínguez, Prudencio May Domínguez, Ofelia Chan Cahuich, María Susana May Kú, Patricio Xool Tun and Virginio Xool Tun. [↩]

- J. Eric S. Thompson, Historia y Religión de los Mayas, 1982, 258-287. To go deeply on the similarities of the above-mentioned conception between the Mesoamerican communities, consult Eduardo Matos Moctezuma (pres.), Dioses del México Antiguo, 2003. [↩]

- Maya writing and translation of the concept are Concepcion Chan Tun, who since the beginning of the 1990s was trained by the National Institute for Adult Education (INEA) to serve its people as literacy in Maya. According to Otto Schuman (Personal communication, 1992), the word is correct, considering that it may be a regional variant that does not alter the meaning. He prefers tan yóok ‘ol kaab (center of the world). In turn, Calepino of Motul proposed tanyol cab (in the middle or in the center of the earth), with yokol cab which translates as “in the world”. For his part, the Maya-Spanish dictionary reprinted by Porrúa draws that yok’kab as yok’ ol kab are equal to saying “in the world,” while so yol kab means “center of the earth” and so yok’ol kab “Center of the world.” See Ramon Arzápalo (ed.), Calepino of Motul. Maya-Spanish dictionary, 1995, 1, 593 and 702; Alfredo Barrera Vasquez (dir.), Maya Dictionary. Maya-Spanish, Spanish-Maya, 2001, 776 and 979. [↩]

- According to linguists, the “ñ” is one of five letters that are not used in the Mayan alphabet, so the correct way to write sky and cloud is not muuñal but muuyal. By asking the xohuaimiloob they indicated that for them the first one is the correct. [↩]

- Juan Gualberto Xool Dominguez, personal communication, march 5 1988. It seems a contradiction to say that the Maya considered a traditional house has four sides equal in size, as is well known that usually the plant is elliptical. But it is not so when you take into consideration its trace on the basis of 4 poles, which form a box, bear the entire top structure, which also favors its famous triangular roof. Each of the poles represents a cardinal point, which must be offered up before occupying the house. [↩]

- From my point of view, this belief in the divine measurement is the reason why the xohuaimi and in general the Mayas of the Yucatan peninsula have the need and the obligation to sowing seeds not by amount, as do many other people, including Cerro Alto, my land in Guerrero, but by rope, agricultural unit of 20 x 20 m. Therefore, while in Guerrero the amount of seed to use determines the size of the cropland, in the Yucatan is the rope to spread that determines the amount of seed to use. Even in cases of non-availability of any of these elements, the cornfield will always be measured by the total amount of corn seed used in that case and in this case by total amount of ropes. [↩]

- Mario May Chan, personal communication, January 6, 2001. [↩]

- In my thesis to opt for a master’s degree in History of Mexico by the Facultad de Filosofía y Letras at UNAM, I will address in detail the analysis of this approach. [↩]

- Mario May Chan, personal communication, April 19, 2006. [↩]

- Conversationalist with friends and strangers of Mayan life, and contributor to several European anthropologists, don Chavo told me in 1988 that he knew more than his colleagues in the surrounding area, because since he was a young boy he had been exploring and researching with their relatives and friends, of all the events of the past. With them, he learned, among other things that the gods of the bearings in the world are: t’uup Balam, to the east; Xoc Balam, in the north; piristun Balam, to the west; ah balantun, south and center cit balantun. In addition, he has in his house several small figures that represent them and daily he gives their offering, water and food. Obviously, he did not allow me to take any photograph of the figures, nor of his notebook, which had a drawing of the sacred ceiba divided into three levels, and that symbolized his idea of the world. I will talk in more detail regarding this, in my thesis for my master’s degree. [↩]

- According to the critical edition of Ramon Arzápalo, op.cit, 34, the word “ah men” led by the end of the sixteenth century as a “master of any art or craft or trade, and official”, but at present is restricted to traditional and folk healer, the men, who knows. [↩]

- Rufino Cauich Kú, personal communication, May 16, 2002. [↩]

- El Libro de los Libros del Chilam Balam, 1978, 129 [↩]

- This idea is certainly reminiscent of the pre-Columbian Maya belief that the south belongs to the lord of death, Ah Puch. See also Maria Cristina Alvarez, Textos coloniales del Libro de Chilam Balam de Chumayel y textos glíficos del Códice de Dresde, 1974, 30-49. [↩]

- According to Villa Rojas, the two cosmogonist versions in reference to the strict vertical order and the vertical-staircase type are present in both groups of Mayan lowlands and the uplands. Therefore, the presence of a certain group of them does not exclude the other in any of the neighboring groups. See Alfonso Villa Rojas, “Los conceptos de espacio y tiempo entre los grupos mayances contemporáneos”, in Miguel León-Portilla, Tiempo y realidad en el pensamiento maya, 1986, 140-147; also J. Eric S. Thompson, op.cit., 242-243. [↩]

- See the prophecy “Episodio de Ah Mucen Cab en un Katún 11 Ahau”, in El Libro de los Libros del Chilam Balam, ed. Cit., 90-91. [↩]

- Pablo Domínguez, personal communication, March 28, 1988. According to this, women should never turn off the fire, much less in the evening, added don Pablo. [↩]

- Alfonso Villa Rojas, “La imagen del cuerpo humano según los mayas de Yucatán”, in Anales de Antropología, Vol. XVII, 1980, t. II, 31-46. For more details on the Indo-American conception concerning the umbilical cord, see Alfredo López Austin, Cuerpo Humano e ideología. Las concepciones de los antiguos nahuas, 1980, t. I, 99-262. [↩]

- Francisca Pacab y Emilia May Pacab, midwifes, personal communication, April 18, 2003. [↩]

- Divided in two parts, “el lenguaje de Zuyua” understands the symbolism of the yucatecans-Maya-power groups. Anyone who would like access to the mat and the throne was to show him their legitimate lineage, their courage and prudence. El Libro de los Libros del Chilam Balam, ed. Cit. 135. [↩]

- According to the “Diccionario Calepino de Motul”, the Word in reference translates into Spanish as follows: “hetzmektah”, -te, sobacar y sustentar. To take or carry babies in the arms, holding them. The same is for wáter pitchers that they carry on their hips. See Ramón Arzápalo, op.cit., 303. The study of the origin of this load custom has given content to two opposing positions: for some, including myself, a pre-Columbian inheritance is undoubted; for others, Aguirre Beltrán for example, is a black contribution to the indigenous cultures to our country. In my masters degree thesis I will explain thoroughly the reason of my position. For the opposite case, see Gonzalo Aguirre Beltrán, Cuijla. Esbozo etnográfico de un pueblo negro, 1974, 73-76. [↩]

- On the order that the turns must have I mention the general reference, as there is not absent the one who affirms that it is not import the course followed while the man ties the destiny and his wife unties it. Between several ceremonies seen, only in one the sides were inverted: the godfather to the left side and the godmother to the right; both carried the child on their left side, as it is observed in the photos. [↩]

- The concept of universal knot is related to that which binds and unifies, but also with what was unleashed by the magic or medicine. For this reason, the knots are one of the elements that characterize the gods of magic, those immobilized by incantations. They also represent, in the Indian tradition, continuity, infinity and immortality, and the inexorable fate. They are a representative of the cosmic law and symbolize to use in its multiple manifestations. Moreover, in its meaning of continuity, knots also refer to a kind of social contract that binds and you can not escape”; Teresa Escobar Rodhe , “los nudos: apuntes para una investigación iconográfica”, en Barbo Dahlgren (ed.), Historia de la Religión en Mesoamérica y áreas afines. 1 Coloquio, 1987, 87-93. [↩]

- El Libro de los Libros del Chilam Balam, ed.cit., .133. [↩]

- Juan Gualberto Xool Domínguez, personal communication, April 11, 1988. [↩]

- According to the prophetic books of Maní, Tizimín and Chumayel, all of which make up the so-called Matichu Chronicle, the precolumbian Mayans referred to the supreme God in a similar manner: Hahal Ku, the true deity, see El Libro de los Libros del Chilam Balam, ed . Cit., 54 et seq. [↩]

- See J. Eric S. Thompson, Grandeza y decadencia de los mayas, 1984; Mercedes de la Garza, El universo sagrado de la serpiente entre los mayas, 1984; Michael D. Coe, Los mayas. Incógnitas y realidades, 1986; Alfonso Villa Rojas, Estudios etnológicos. Los mayas, 1985; Martha Ilia Nájera, El don de la sangre en el equilibrio cósmico. El sacrificio y el auto sacrificio sangriento entre los antiguos mayas, 1987; Laura Elena Sotelo Santos, Las ideas cosmológicas mayas en el siglo XVI, 1988. [↩]

- Prudencio May Domínguez, personal communication, August 4, 1988. [↩]

- Victoriano Chan May, personal communication, July 22, 1989. [↩]

- Juan Gualberto Xool Domínguez, Moisés Chan Couoh y Baltasar chan Cahuich, personal communication, June 3, 1995. [↩]

- El Libro de los Libros del Chilam Balam, ed. Cit., 111-112. [↩]

- Version of María Susana May Kú, according to the conversations held with her mother and grandmother on the father side, Victoria Kú Várguez and Teófila Chan. Personal Communication, January 6, 2004. [↩]

- Ofelia Chan Cauich, personal communication, May 18, 1991. [↩]